Experts say billions in a multi-year plan won’t go far enough to address infrastructure repairs and upkeep.

With help from the federal government, Illinois will put more than $2 billion toward infrastructure projects this year across the state’s network of roads and bridges. But that network is underfunded by billions more, and what’s the state has pledged is a far cry from fixing that.

Just days before the budget passed in May, Gov. Bruce Rauner took a drive up to Peoria, stood across from a worn-down bridge over the Illinois River, and told reporters the state was going to invest $11 billion total over the next six years in roads and bridges.

What he talked about is spelled out in the Department of Transportation’s Multi-Year Plan. It’s how the state maps out what kind of road work it’s going to do over the next several years. The plan is pretty routine – it gets updated from year-to-year with the most pressing projects.

But what’s interesting this year is that Illinois is changing its road strategy altogether. Before, construction crews used to just fix the roads and bridges that were in the worst shape. Now, IDOT plans to do regular maintenance of state routes to avoid costly future repairs.

While experts say that’s a good first step, Kevin Burke of the Illinois Asphalt and Pavement Association believes neither the billions of dollars nor the new strategy are going to cut it, because Illinois has underfunded its roads for so long.

“We have not adequately funded our infrastructure since 2000,” he said.

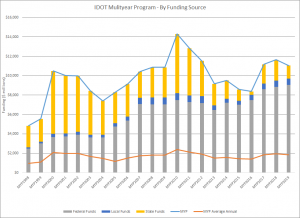

Though it shares road costs with the federal and local governments, Burke says Illinois has gradually cut its share since then, while federal dollars have steadily accelerated, so much so that 80 percent of IDOT’s Multi-Year Plan funding comes from Washington, D.C.

Erin Aleman, director of IDOT’s Office of Planning and Programming, agrees with Burke. As one of the state’s leading transportation planners, she too says there just isn’t enough revenue to do the work that needs to be done.

“I’d say less than 10 percent of our projects expand the system that we have right now. Ninety percent really focuses on maintaining,” Aleman said.

Since the state last paid for a majority of road costs in 2000, construction costs have increased 61 percent, according to the Federal Highway Administration. State funds for transportation, however, have fluctuated and on average, remained largely static in that amount of time.

This kind of works like the pension problem: pension costs increase over time, but the state’s appropriation for those costs have simply not kept up. That’s how we end up billions behind in that arena and this one.

Though far less expensive by comparison, even maintaining the roads isn’t cheap. To show just how stretched Illinois’ infrastructure budget is. IDOT Officials are shooting for Illinois roads to be at or better than a “fair” condition between now and 2024. That’s the second to last rating on its pavement condition scale.

Burke says, if that’s the goal, a commute probably won’t get any better; in fact, he warns Illinois roads are probably going get a lot worse.

“You’re gonna see a lot of cracking; it’s gonna be a rougher ride,” he said. “There’ll probably be better chances of potholes, especially in the winter months when we have freeze-thaw cycles.”

But now that IDOT plans to keep up with that maintenance, officials including Illinois Transportation Secretary Randy Blankenhorn, are confident the roads will hold up better for longer.

“This program doesn’t get us to where we need to be, but it’s a good step forward in maintaining what we have and making sure we’re giving true value to the people of Illinois,” Blankenhorn said at a press event in May.

But the question remains: what will regular road maintenance really do, if anything? Dave Bender, a road engineering expert from the American.

“Overlaying with additional asphalt or other patching of concrete simply does not address the decay of our system,” Bender said.

As cars and trucks whizzed by just a few hundred feet from him, Bender said the interstate roads they were driving over are long overdue for an upgrade.

“They [the interstates] were built in the ’50s and ’60s. The Interstate Highway System was only designed to last for about 40 years: today, we’re on year 60,” Bender said. “The foundation, which is several feet deep, is starting to decay.”

Bender likened the situation to an old house: periodically, its foundation needs to be repaired or even replaced for it to stay standing.

“If they think fixing the house is similar to what we’re doing with the Illinois roads, they’d be on putting shingles on a new house and thinking everything is ready to go,” Bender said.

Bender estimates that the interstate system alone in Illinois would take some $55 to $60 billion to replace completely. At the state’s current spending on interstate construction, he says it would take hundreds of years to complete that project.The conditions of local roads — the ones that wind through Illinois towns big and small and that get drivers to the interstates in the first place — are often in disrepair as well.

“The locals are almost on their own,” Bender said. “There’s no additional increase in it [the Multi-Year Plan] for them. They have been hurting very, very greatly as well.”

Jeff Ronaldson, an engineer for Will County, is one of those locals. He said Will County roads are in pretty good shape for now, but traffic numbers there have picked up recently.

“We have a lot of capacity improvements we need to fund,” Ronaldson said. “So, of course, any additional dollars we can capture to move those projects forward is what we’re striving for.”

Further south in Springfield, Director of Public Works Mark Mahoney is on a similar path. Though the city managed to pay for some needed roadwork by raising its sales tax, Mahoney says the long-term funding problem hasn’t gone away.

“There’s such a dire need right now,” he said. “It’s a ‘robbing Peter to pay Paul’ kind of situation where you’re having to make choices with what you have.”

So, it’s pretty clear at this point: Illinois needs to put more money into its roads. Experts and officials agree this means a new revenue source. But what the source could be is unclear. Past infrastructure plans have relied on changes like higher license plate fees and hiking alcohol taxes.

As a way to stop state officials from using transportation money for other state government costs, as they often did in the past, Illinois voters overwhelmingly approved a transportation “lockbox” amendment to the state’s Constitution in 2016. That amendment requires any transportation-related revenue the state collects to be spent only on transportation-related costs. But that doesn’t generate any new money, which experts say is the real heart of the problem.

More recently, officials have tossed around ideas like raising the gas tax, something the state hasn’t done in more than 25 years. Another idea is to tax people according to how many miles they drive. But as Laurence Msall of the Chicago Civic Federation said, none of those ideas are particularly popular.

“There has been little political will to tie the state’s infrastructure and capital needs to paying for them,” Msall said.

Msall tied the lack of will to Illinois’ recent income tax hike, which coincided with property tax increases in most places. He said Illinois is also running out of room to borrow. So if the state needs new money from taxpayers, Msall said, it’ll have to show them they’ll get something out of it.

“It’s incumbent on legislators, and the transportation advocates to identify what people are going to get as a result of that increase,” Msall reasoned.

For now, Illinois remains behind on its road spending. But as the experts said, we rely on the modern road system for just about everything. They postulate the system will eventually not be reliable or even available unless funding is somehow addressed.